When it comes to microbes, “everything is everywhere”

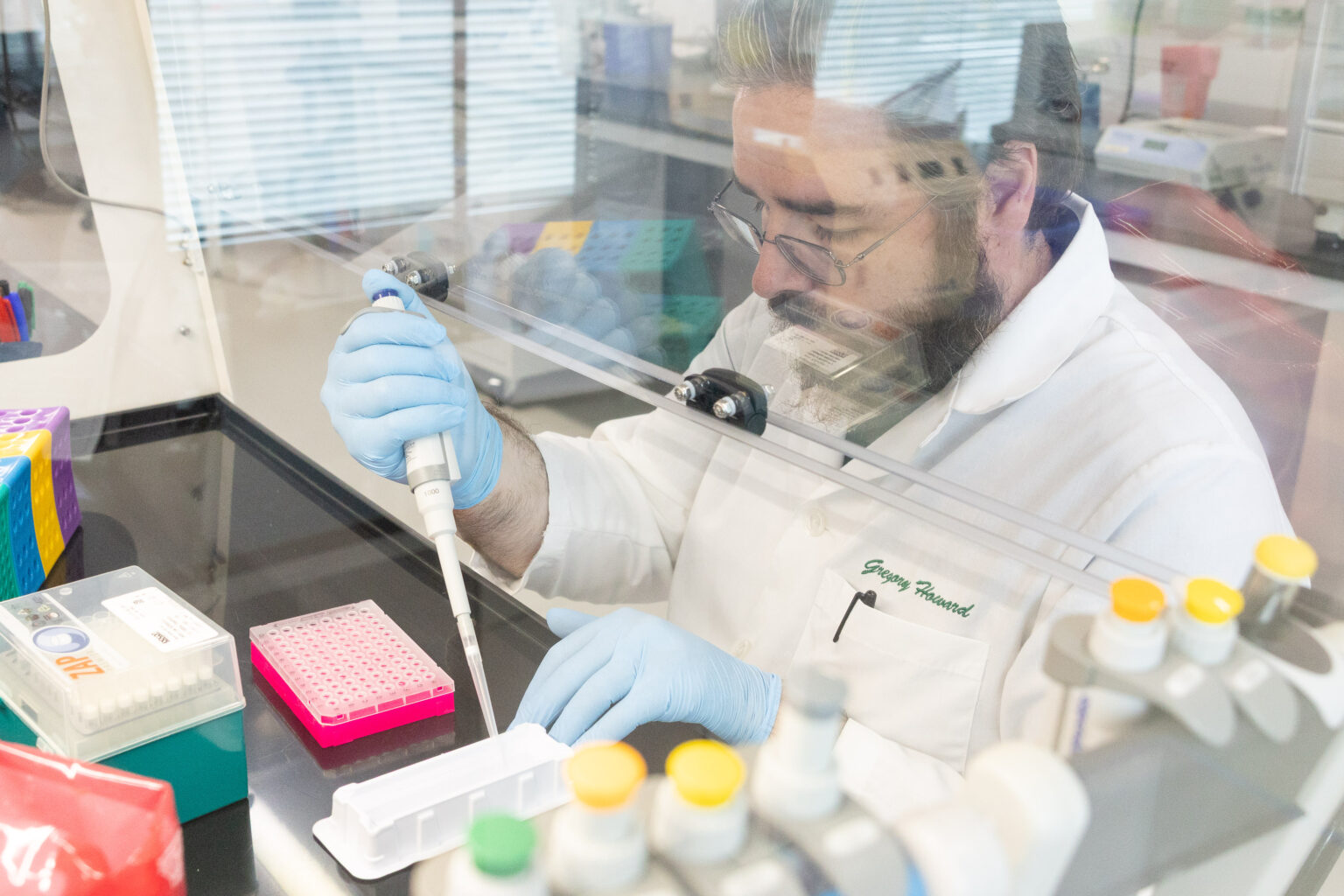

Marc Demeter, our Director of Market Development, shares his expertise on managing microbial threats in the oil and gas industry.

In oil & gas, managing invisible threats means high-stakes decisions every day.

In this blog series, Marc Demeter, Director of Market Development for Oil & Gas, tackles common misperceptions and shares expertise to help you tackle microbial challenges with clarity and confidence.

One of the most common questions I hear is, “What microbes are unique to my basin or region?”

It’s a fair question. Regional differences shape much of what we know about the world. Travel 2000 miles in any direction and you’re likely to encounter a new climate, different trees and animals, maybe even a different language or culture.

In oil and gas, we also talk about basins as unique. Some produce heavy oil versus light oil, or oil versus gas. We also observe different stratigraphy, water cuts, and reservoir temperatures. If geology and fluids vary by basin, it seems logical to assume the microbial populations do too. Maybe the DJ basin harbors a souring organism you’d never encounter in the Marcellus or Eagle Ford.

But after evaluating microbial communities from oilfields all over the world—North America, the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, North Africa, and the Middle East—I can say with confidence: microbes don’t follow the same regional rules. There isn’t a special “Permian bug” that only causes corrosion there. You also can’t look at the species in a sample and guess which basin it came from.

Sorry, your well isn’t special. And that’s okay!

That idea would make our jobs easier, but it’s not how microbes work.

The reason comes down to size

A microbial cell is only one to ten microns across.

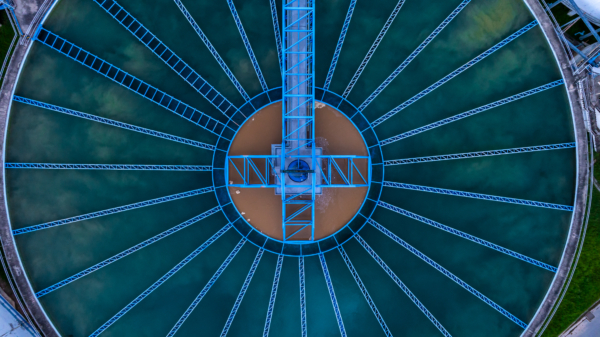

To a microbe, even a few millimeters can be the difference between two very different worlds. Take a slimy biofilm as an example. In a biofilm just a few millimeters thick, you can find multiple distinct microbial communities stacked on top of each other. At the oxygen-rich surface, aerobic hydrocarbon degraders flourish.

A little deeper, oxygen is depleted and acid-producing bacteria take over, feeding sulfate reducers that generate H₂S in the anoxic zone. The waste of one microbe becomes the food of another. Each layer is its own small neighborhood, shaped by what’s available. To microbes, these microniches matter much more than whether they are in Texas or North Dakota.

This ties directly to a principle first described by Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck: “Everything is everywhere, but the environment selects.”

Microbes spread easily and are found all over the globe.

They move through air, water, and even hitchhike on animals. What matters is not whether a species is present, but whether the local conditions allow it to grow.

Oil reservoirs show this well. Many reservoirs were once oceans, so we often find salt-loving marine microbes in them. But once drilling and production begin, the chemistry changes. New nutrients and chemicals are introduced. That shift creates opportunities for different organisms—like acid producers, sulfate reducers, methanogens, and iron reducers.

So while basins differ in geology and fluids, the microbes we see are not regional specialties. Instead, they are shaped by local conditions and tiny microniches. In short: microbes may be everywhere, but only the environment decides which ones survive and thrive.

While the microbes themselves may not be unique, community composition from various wells and assets will be different.

Assessing that community composition and monitoring for shifts or changes can tell a story and serve as the backbone of microbial risk management.

What does this mean for you?

Focus on where microbes can enter your system, and watch for physical and chemical clues that signal which groups will grow.

For example, a moderate temperature reservoir fractured with recycled produced water that is high in sulfate and iron is ideal for sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB). Without adequate treatment, expect iron sulfides, H₂S, and corrosion during production.

Ask two simple questions:

- what was the source of microbial entry, and

- what changed the conditions to favor them?

In this case, it’s the thousands of barrels of produced water used during completion.

This is why testing source waters with microbial diagnostic tools is so valuable.

Knowing which microbes you are about to introduce—together with the water chemistry—lets you mitigate risks before they establish downhole.

Remember: everything is everywhere, but the environment selects. Plan each step with the microbial health of your asset in mind.

Want to learn more? Our next in-person Polytechnic is in Denver on November 4. Join your peers and our expert instructors for a full-day session on oilfield microbiology.

Explore Luminultra resources

Make confident decisions with trusted expertise.

Discover webinars, whitepapers and expert articles focused on microbial control.